by Amy Caron

We’ve been talking about healthcare delivery systems locally and by country, but let’s take it all the way back to health disparities. We’ve seen in a previous post that minority groups, racially, socioeconomically and otherwise, experience poorer health outcomes, but why? What makes some groups healthier than others?

We’ve been talking about healthcare delivery systems locally and by country, but let’s take it all the way back to health disparities. We’ve seen in a previous post that minority groups, racially, socioeconomically and otherwise, experience poorer health outcomes, but why? What makes some groups healthier than others?

Social determinants of health are conditions in the

environments in which people live, learn, and work that affect health and

quality of life. Settings, like schools, churches, workplaces and neighborhoods

along with the patterns of social engagement and sense of security in those

neighborhoods all have an influence on health outcomes.

The framework for examining the social determinants of

health is:

Socioeconomic/political context:

- Culture

- Poverty

- Religion

- Labor market

- Education

- Social norms and attitudes

Structural context:

- Race

- Income

- Education

- Gender

- Housing

- Food

These are similar determinants we examine access to power

and privilege in the Web of Oppression, so we can look at health through the

same lens. The closer individuals are to the center the better the health

outcomes.

When we talk about health and health outcomes, we mustn’t

think narrowly. Simply supplying access to health insurance or health care

services addresses only a part of the problem because oppression and health are

connected.

The issue isn’t just health insurance or how healthcare is

delivered. It’s the cause behind the cause.

For example, causes of infant mortality in developed countries have been found to be:

- racism-related stress and socioeconomic hardship (Giscombe & Lobel, 2005)

- high prevalence of low income among women who experience serious hardships during pregnancy (Braveman et al., 2010)

- high poverty rates and lack of access to a socialized health care system, as is the case on the United States (Tillet, 2010)

- significant correlation of high poverty rates with infant mortality rates among minority and white mothers in the US (Simms, Simms, & Bruce, 2007)

- significant correlation among poverty level, racial composition of geographic areas, and infant mortality rates (Eudy, 2009)

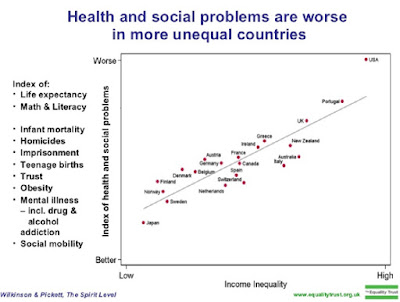

- high correlation of inequality and child relative poverty with infant mortality rates in rich societies (Pickett & Wilkinson, 2007).

Good health for all cannot exist in an unequal society, so

healthcare cannot be seen strictly as a positive right. Infringement on life,

liberty and the pursuit of happiness will and does have an impact on health and

therefore supports the case for the legislation of healthcare. Because

healthcare can be tied to negative rights, the need for healthcare to be seen as

a human right in the United States becomes difficult to argue. Looking at this graph, it's a topic of urgency.

No comments:

Post a Comment